The Kibitka is one of the most advanced prefabricated and demountable

dwelling ever to evolve in a traditional culture. Its form and

construction are dominated by the requirements of demounting,

transportation and erection. It consists of an external envelope supported

on a sturdy frame assembled from standard elements.

The Kibitka is one of the most advanced prefabricated and demountable

dwelling ever to evolve in a traditional culture. Its form and

construction are dominated by the requirements of demounting,

transportation and erection. It consists of an external envelope supported

on a sturdy frame assembled from standard elements.

- Turkic Kibitka

There are two principal types of kibitka; the felt covered

cylindro-conical type used by Mongol peoples and by some Turkish speaking

tribes of Northern Central Asia and the cylindro-domical type found among

Turkish speaking tribes of Western and Southern Siberia such as the

Kirghiz Uzbeg and Turkmen.

There are two principal types of kibitka; the felt covered

cylindro-conical type used by Mongol peoples and by some Turkish speaking

tribes of Northern Central Asia and the cylindro-domical type found among

Turkish speaking tribes of Western and Southern Siberia such as the

Kirghiz Uzbeg and Turkmen.

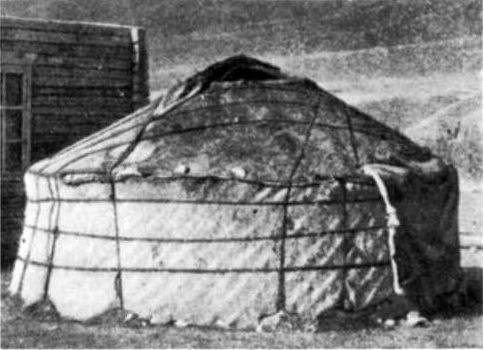

- Mongol kibitka

For the past four hundred years, kibitkas have been built according to the

same structural principles, using the same methods, and employed in much

the same way. The circular geometry with the framing arranged radially

allows the frame elements, except at the entrance, to be simplified into a

few standard building components and this in turn makes for economies in

their manufacture.

For the past four hundred years, kibitkas have been built according to the

same structural principles, using the same methods, and employed in much

the same way. The circular geometry with the framing arranged radially

allows the frame elements, except at the entrance, to be simplified into a

few standard building components and this in turn makes for economies in

their manufacture.

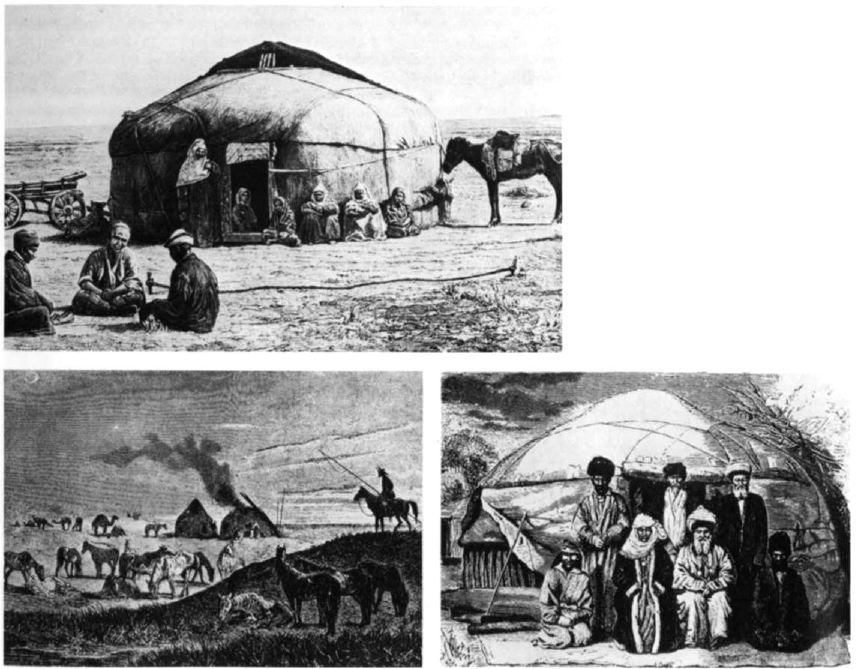

- Kirghiz encampment on the Siberian steppe observed by Humboldt, early 19th centuy.

- Scene on the Kirghiz steppe circa 1893.

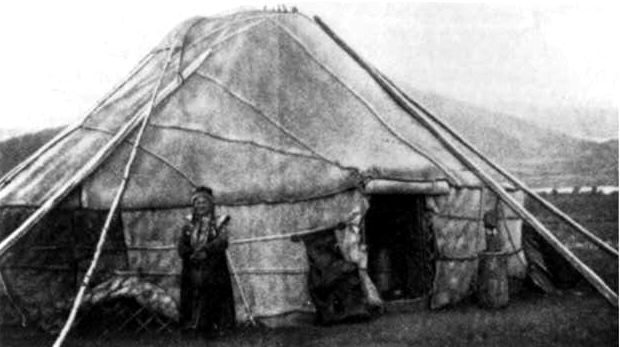

- Unlatticed cylindro-domical kibitka of the Central Asiatic Kirghiz, circa 1893.

Several related forms occur about the periphery of the kibitka zone: in

Iran the Yomut gotikme and the Shah Savan alachigh tents preserve the

dome-shaped roof of the Turkic type but lack the lattice wall frame. These

abbreviated kibitkas provide links with the Turkmen kibitka and the

dome-shaped tents of Iran, Turkey, Iraq and Syria and reappears again in

Northern Tibet among people of Mongolian background.

Several related forms occur about the periphery of the kibitka zone: in

Iran the Yomut gotikme and the Shah Savan alachigh tents preserve the

dome-shaped roof of the Turkic type but lack the lattice wall frame. These

abbreviated kibitkas provide links with the Turkmen kibitka and the

dome-shaped tents of Iran, Turkey, Iraq and Syria and reappears again in

Northern Tibet among people of Mongolian background.

- Unlatticed Kizlitsi cylindrical tent. This is a debased form of kibitka which nevertheless illustrates the type of construction which may have been employed for early cylindrical tents.

The kibitka might have developed from the covered waggons which served as the early homes of nomadic pastoralists. It was customary to transport the kibitkas of important Scythian persons on carts.

- Mongol yurts transported on waggons, 13th century reconstruction.

This transition from a settled to a nomadic pastoral mode must have been

crucial for the emergence of a kibitka type of light portable dwelling.

The early nomads probably lived in elaborate covered waggons sometimes

with two or even three compartments, but at some later stage a lightweight

portable tent came into being.

This transition from a settled to a nomadic pastoral mode must have been

crucial for the emergence of a kibitka type of light portable dwelling.

The early nomads probably lived in elaborate covered waggons sometimes

with two or even three compartments, but at some later stage a lightweight

portable tent came into being.

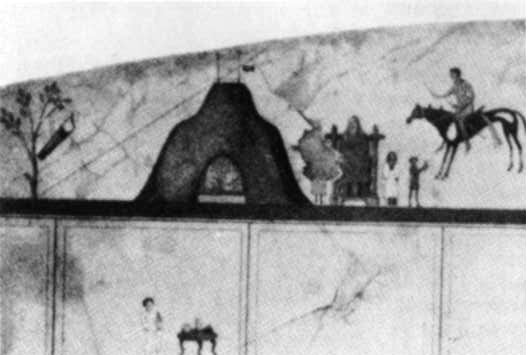

- Wall painting of a tent on a grave at Kerch 1st-2nd century AD.

- Drawing by Friar Rubruck of tents which he saw when he visited the Mongol court in 1253.

The roof ring is the most important distinguishing feature of the kibitka

for it is not found in any other type. It also varies from one ethnic

group to another. The roof ring is an ingeniouss constructional device

which overcomes several deficiencies of the conical tent.

The roof ring is the most important distinguishing feature of the kibitka

for it is not found in any other type. It also varies from one ethnic

group to another. The roof ring is an ingeniouss constructional device

which overcomes several deficiencies of the conical tent.

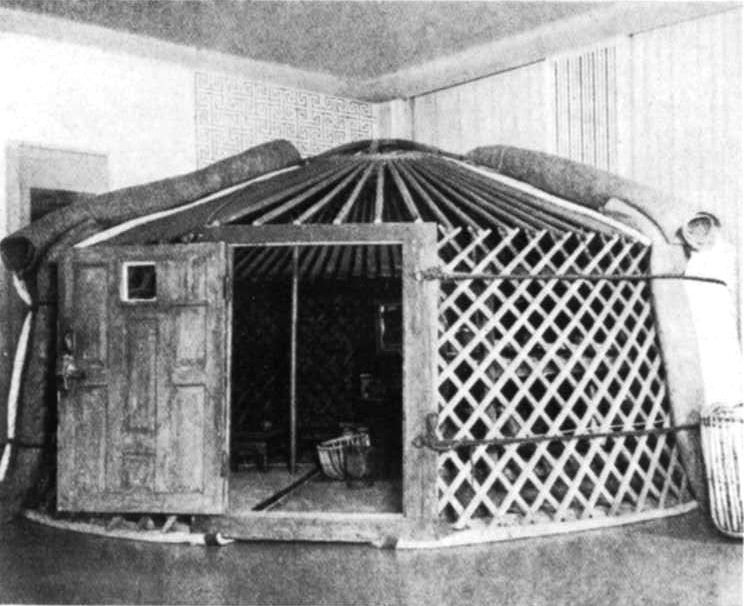

- Kirghiz kibitka, Afghanistan, with the felt covering removed to expose the light frame.

- Frame of the Kazak kibitka of West Mongolia.

- Kazak lattice wall hurdles.

The roof ring admits light and air to the interior, allows smoke from the

central fire to escape, and also serves as a chronometer. The smoke hole

prevents great differences of air pressure and so reduces the wind load on

the tent frame.

The roof ring admits light and air to the interior, allows smoke from the

central fire to escape, and also serves as a chronometer. The smoke hole

prevents great differences of air pressure and so reduces the wind load on

the tent frame.

- Erection of a Mongol kibitka; attachment of roof struts to the lattice wall hurdles.

- felt cover is lifted onto roof.

- tent cover is secured by ropes.

The number of layers used to cover the tent frame depends on temperature.

During winter two or even three layers of felt may be added as protection

against the cold, whereas in summer the side felts may be raised a half

metre or so off the ground to ventilate the interior.

The number of layers used to cover the tent frame depends on temperature.

During winter two or even three layers of felt may be added as protection

against the cold, whereas in summer the side felts may be raised a half

metre or so off the ground to ventilate the interior.

- Felt cover rope fastenings on a Kirghiz kibitka, Afghanistan.

- Roof fastenings of a Kazak kibitka seen from below.

The arrangement of the kibitka's interior space expresses two principles.

First, practical household and work activities are relegated to the front

of the tent in the vicinity of the door, and second, social, ceremonial

and symbolic functions take place towards the rear of the tent.

The arrangement of the kibitka's interior space expresses two principles.

First, practical household and work activities are relegated to the front

of the tent in the vicinity of the door, and second, social, ceremonial

and symbolic functions take place towards the rear of the tent.

- Plan of an Altai Tartar kibitka.

The kibitka sub-types are distinguished by differences in the shape of the

roof-ring, the attachment of the roof poles, the material of the wall

cover, the manner and sequence in which wall covers are applied, the

disposition of the cover above the roof-ring, the kind of door and the

base strip around the outside of the tent. The differentiation occurs

along ethnological lines.

The kibitka sub-types are distinguished by differences in the shape of the

roof-ring, the attachment of the roof poles, the material of the wall

cover, the manner and sequence in which wall covers are applied, the

disposition of the cover above the roof-ring, the kind of door and the

base strip around the outside of the tent. The differentiation occurs

along ethnological lines.

- Types of kibitka roof rings: Tuvinsti, Torgout, Dzkhachin groups, Western Khalkha groups and some Buryat and Santful groups which have been influenced by the Khalkhas.

- Mongols, Kazaks and Transbaikalian Buryat.

- Mongol.

- Mongol.

- Shah Savan, Iran.

- Transbaikalian Buryat.

Among the Turkish tribes, the Kazaks of West Mongolia, the centrral and

western groups of Khalkhas and the West Mongolian Oirats, and Buryats, the

roof poles are inserted in holes around the outside of the roof-ring.

Among the Turkish tribes, the Kazaks of West Mongolia, the centrral and

western groups of Khalkhas and the West Mongolian Oirats, and Buryats, the

roof poles are inserted in holes around the outside of the roof-ring.

- Tuvintsi and Buryat roof rings.

The form of the roof-ring is the most important distinguishing feature of

sub-types within the family of kibitka tents. Eight types of roof-rings

have been recorded in Western Mongolia alone and a further three in

Southeastern Mongolia.

The form of the roof-ring is the most important distinguishing feature of

sub-types within the family of kibitka tents. Eight types of roof-rings

have been recorded in Western Mongolia alone and a further three in

Southeastern Mongolia.

- Large Mongol roof ring supported by timber posts.

The latticed cylindrical tents of the Altai, Khakassi and Tuvintsi are

related to the Mongol kibitka. The conical shape and construction of their

roofs is similar to the Buryat yurt which follows the Mongol pattern.

The latticed cylindrical tents of the Altai, Khakassi and Tuvintsi are

related to the Mongol kibitka. The conical shape and construction of their

roofs is similar to the Buryat yurt which follows the Mongol pattern.

- Latticed Altai Kizhi cylindrical tent covered with felt.

- Tuvinsti cylindrical tent.

The kibitka-like tent in which a simplified wall of vertical posts or

extended roof- ribs replace the complicated lattice occurs in both the

North Altai and upper Yenisei region, and in North Iran, North Afghanistan

andTurkestan.

The kibitka-like tent in which a simplified wall of vertical posts or

extended roof- ribs replace the complicated lattice occurs in both the

North Altai and upper Yenisei region, and in North Iran, North Afghanistan

andTurkestan.

- Interior of an Altai Yurt.

It is suggested that the latticed kibitka was adopted by the Turks of

Southern Siberia from the Mongols.

It is suggested that the latticed kibitka was adopted by the Turks of

Southern Siberia from the Mongols.

- Tuvintsi cylindrical tent.

It is likely that the unlatticed cylindrical tents derived fom the

latticed ones.

It is likely that the unlatticed cylindrical tents derived fom the

latticed ones.

- Tuvintsi tent frame.

The Sagaitsi unlatticed tent framework is an odd construction, having an

enlarged roof-ring typical of the kibitka supported on a crude two-pole

foundation which has one of the pole butts resting on top of the wall

rail.

The Sagaitsi unlatticed tent framework is an odd construction, having an

enlarged roof-ring typical of the kibitka supported on a crude two-pole

foundation which has one of the pole butts resting on top of the wall

rail.

- Sagaitsi unlatticed cylindro-conical dwelling.

Modifications of the kibitka form arise in two ways, the complicated

lattice system may be simplified, or alternatively it may be eliminated

altogether.

Modifications of the kibitka form arise in two ways, the complicated

lattice system may be simplified, or alternatively it may be eliminated

altogether.

- Teleuti unlatticed cylindro-conical dwelling.

The Kötük Gotikme and Götikme tents of the Yomut Turkmen,

and the alachigh tents of the Shah Savan and their neighbours and Qaradagi

of North Iran consist of a domical roof frame similar to that of the

Turkmen kibitka, without the trellis wall.

The Kötük Gotikme and Götikme tents of the Yomut Turkmen,

and the alachigh tents of the Shah Savan and their neighbours and Qaradagi

of North Iran consist of a domical roof frame similar to that of the

Turkmen kibitka, without the trellis wall.

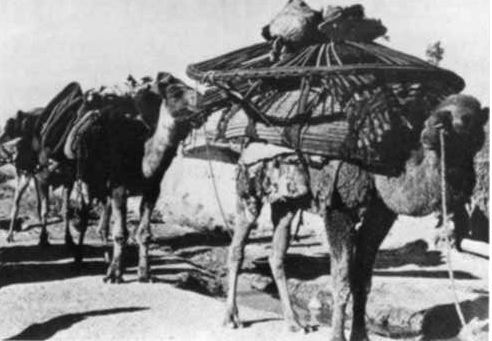

- Transport of a single Yomut tent.

Although the kibitka is well suited to the nomadic existence of the steppe pastoralist, it is far from being an ideal dwelling.

- The Yomut tent frame during erection.

- Lashing of the felt covers to the tent frame.

- Frame of the Shah Savan alachigh tent.