Anthony Ricciardi's "Lessons From An Ecological Crisis: The Brown Spruce

Longhorned Beetle (BSLB) Debate[1]" is a deeply disappointing tract.

Seeking to draw larger lessons from the recent debates on the subject, its

primary failings are that Ricciardi ignores the large number of legitimate

concerns raised by environmentalists, and sets up a series of straw men -

so-called 'fallacies' which most environmentalists never claimed. These he

proceeds to demolish with merry abandon. As entertaining an exercise as

this may be, it bears little relation to the debate (past and present)

with regard to this issue nor does it address or shed light on the

substantive issues raised by ecologists and environmentalists.

Undermining his attempt to develop a serious discussion on this issue, is

Ricciardi's injudicious lumping of the sources of his material. These

sources include both well-considered essays by knowledgeable and

creditable sources, with comments (sometimes informal) by those with

little knowledge of the issues. By this means all "environmental

activists" are tarred by the same brush. While an examination of, say,

letters to the editor pages, the archives of listservers, or the records

of call-in talk shows on this issue, would clearly reveal many legitimate

and crackpot notions, this is not at all the same as a considered analysis

of the substantive and legitimate ecological and public-policy issues

raised by this debate. In his paper Ricciardi unfortunately misses an

opportunity to do the latter.

Let us briefly address the fallacies of Ricciardi's "fallacies." Before

doing so, let me address one issue at the outset, namely Mr. Ricciardi's

assertion that, "trained ecologists, with few exceptions, were

conspicuously silent in the debate," which attempts to enshrine a false

polarity which does not exist. The vast majority of members of Friends of

Point Pleasant Park (FPPP) are academics, scientists, horticulturists, and

serious naturalists many with extensive biological, ecological, and

entomological backgrounds and experience, and many with PhD's. This

attempt to frame the debate in these terms would, if left unchallenged,

distort the nature of the academic, social, and political discourse around

this issue.

In particular I am a trained ecologist (see brief note at the end of this

article). Moreover, for the past year, with the assistance of the Nova

Scotia Museum, I have been conducting my own research on the entomology of

Point Pleasant Park.

Let us now proceed to the matter at hand.

So-called Fallacy #1: If predators are present, the invader won't become apest.

The first straw man. Neither Friends of Point Pleasant Park nor I have

ever argued this.

The first point to be deconstructed here is the word "pest." What is a

pest? The Plant Protection Act, under whose aegis the Canadian Food

Inspection Agency (CFIA) has been acting, defines a pest as, "any thing

that is injurious or potentially injurious, whether directly or

indirectly, to plants or to products or by-products of plants [2]". It has

always been the position of FPPP that this definition is vastly too broad.

Strict adherence to this definition would encompass every native

herbivorous animal to be found in Canada - and many others beside. Are not

all native woodpeckers, finches, rodents, ungulates, etc. 'injurious' to

plants? In this regard it is important to note that the word 'pest' is an

economic rather than an ecological term. If one removes all the potential

'pests' no normal ecosystem will remain.

|

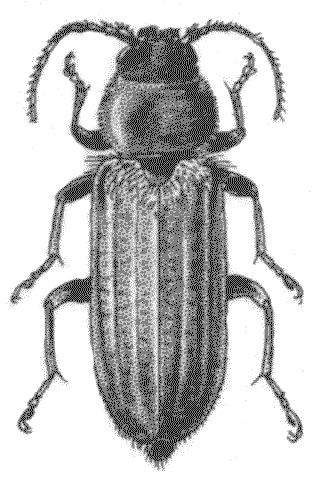

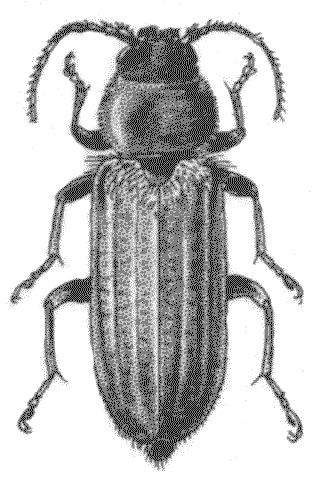

The metallic wood-boring beetle,

Buprestis maculiventris.

|

Reason, then, dictates that one should more properly establish what

constitutes a 'pest'. In Nova Scotia we have a large number of native

insects whose ecology is, in many respects, very similar to that of the

BSLB (Tetropium fuscum), that is to say they feed on severely stressed and

dying trees hastening their demise. These include many of the some 95

species of Longhorn Beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) found in the

province as well as many species of Metallic Woodboring Beetles

(Coleoptera: Bupestridae), woodboring Sawyer Wasps (Hymenoptera:

Siricidae) and many species of Bark-boring Beetles (Coleoptera:

Scolytidae). These groups, moreover, are all well-represented in the

forests of Point Pleasant Park (PPP). I and other researchers have found

at least nine species of Longhorn Beetles (Rhagium inquisitor, Asemum

striatum, Xylotrechus undulatus, Tetropium fuscum, T. cinnamopterum, Evodinus monticola, Anthophylax viridis, Cosmosalia chrysochoma, and Pogonocherus penicillatus); three species of metallic woodboring beetles

(Chrysobothris pusilla, Melanophila fulvoguttata, and Buprestis maculiventris)

several species of siricids (including Urocerus cressoni and Sirex sp.) and

over 20 species of scolytids [3].

|

|

The Pine Stump Borer, Asemum striatum.

|

If the BSLB is simply one additional member in a diverse fauna feeding on

dying trees - as all European research on this species indicates, and as

is true of virtually the entire cerambycid family - then it maqkes no

sense to single it out as a pest from the complete species assemblage. Dr.

Wojciech Zabecki from the Faculty of Forestry, in Krakow, Poland, a

published authority on this and other species of cerambycids writes:"

"This species (T. fuscum) is found abundantly only in older stands of trees and those

which are weakened by various anthropogenetic [human-caused] or

environmental factors. It does not attack healthy trees.[4]"

The Norwegian Forest Research Institute writes :

"The beetle's (T. fuscum) importance as a harmful pest on timber is therefore not

large. Its attack on a living forest is also of small importance. Trees

that are chosen are as a rule highly weakened, and many will surely die of

other causes even if the bark beetle doesn't establish itself there.[5]"

[It's worth noting here that such assesments of the relatively benign

impact of this species on the environment have been consistently ignored

or downplayed by the CFIA in it's Plant Health Risk Assesment.[6]]

Thus, as a species attacking dying trees, even if eliminated, its absence

would have little impact on the survival (or not) of such trees since a

large number of other indigenous insects are already hastening their

demise. An insect that attacks solely dying trees can clearly not be

considered a threat to healthy forests and plantations, particularly since

a plenitude of native species do exactly the same thing. Evidence that the

BSLB is doing anything else (i.e. changing its basic ecology to attack

healthy trees) is conspicuously absent.

This moreover, is hardly likely to be accidental. Even a cursory

examination of the literature relating to resinosis in spruce trees shows

that healthy trees have ample resources to deal with potential insect

invaders of this type, essentially drowning larvae in resin or gassing

them with turpenes [7]. Only already significantly weakened trees are

susceptible and attractive to this insect community and succumb to their

activities. Hence attacking healthy trees is not a ready ecological option

for BSLB, or for cerambycids in general. To presume otherwise would fly in

the face everything known about the physiology of conifers and the ecology

and behaviour of the insect group worldwide. E Gorton Linsley, author of

the most authoritative volume on the ecology of North American cerambycids

says:

"Cerambycids are primarily forest insects ... They play a beneficial role

there in helping to reduce dead and dying trees, broken branches, etc. to

humus.[8]"

To claim otherwise, that the BSLB are attacking healthy trees, would

involve marshalling convincing evidence to the contrary. Such evidence is

nowhere to be seen, neither by the CFIA nor by Ricciardi. Consequently

there is no evidence that the BSLB qualifies under any reasonable

definition of "pest."

What, then, is the position of FPPP with regard to predators and predation

and its potential significance?

|

The Checkered Beetle,

Thanasimus dubius.

|

Fact 1: In the summer of 2000, PPP had extensive populations of predators

of wood-and bark-boring insects. I found four species of Checkered Beetles

(Coleoptera: Cleridae) there [9] (Thanasimus dubius, Enoclerus nigripes,

Phlogosternus dislocatus, and Zenodosus sanguineus) which for a significant

time period in the summer of 2000 were amongst the most abundant group of

beetles to be seen in the Park. These are known and well documented

predators of cerambycids, with both adults and larvae attacking the

cerambycid larvae [10]. They are known predators of the genus Tetropium. And

where are these predators found? Precisely on the ill trees that exhibit

bore-holes and resinosis.

|

|

A braconid wasp of the genus Atanycolus sp.

|

Also, very abundant in the Park in 2000 were several species of braconid

wasps (genus Atanycolus; not yet identified to species) and several

species of Ichneumon wasps (not yet determined), both groups of parasitic

wasps many of which are well-known predators of cerambycids [11]. Again, where

do these wasps conngregate in numbers, and where does one see them

ovipositing (laying eggs)? Precisely on the same ill trees. In addition

the Park is the home of a significant population of Downy Woodpeckers

(Picoides pubescens) and Red-breasted Nuthatches (Sitta canadensis), which

can readily be observed foraging for insects on dead and dying trees.

|

|

The Red-breasted Nuthatch, Sitta canadensis.

|

Most recently I have observed significant numbers of the hister beetle

Teretrius sp., which Arnet & Thomas [12] say are "predators of wood-boring

Coleoptrea," under the bark of spruce trees.

Fact 2: The available data on BSLB populations indicate that there has

been a decrease in their numbers over the last decade. An extensive

trapping program in PPP run by the NS Department of Natural Resources

(DNR) caught six Tetropium fuscum in 2000 [13] (only one T. fuscum was found

outside Pt. Pleasant Park). While we have only (perhaps incomplete) raw

data to work with, DNR trapped from (a minimum of) May 24-July 20 (8 weeks

& 1 day) with 30 traps (of 4 types) [14]. This leads to an index of population

of .0035 beetles/trap night. This is an index which reflects the 2000

population density of T. fuscum in PPP.

In 1990 Stephanie Robertson trapped for 5 weeks = 35 days with 90 traps

(three types) and caught 17 T. fuscum = .0054 beetles/trap night [15]. Thus

the current population is only 65% of that recorded in 1990. Over a decade

this simple indicator shows that the population of T. fuscum has declined

by 35%.

However, Robertson's study was examining scolytid beetles in the Park.

Cerambycids were incidental to the main research so that only a portion of

those trapped were retained in the collection [16] (the remainder were

discarded). There is, of course, no way to recover this lost data,

however, Robertson, on reflection, believes that the retained specimens

represent cerambycid data from only 10% of her traps (the museum specimens

are from only 3 of the 30 locations where traps were set). Thus the

decline in numbers is certainly even greater, possibly very much greater

(i.e. potentially a decline to 6.5% of previous levels).

Of course, it makes little sense to cling dogmatically to these specific

numbers since sample sizes are small, the trapping data would need to be

normalized over different types of traps, some data are unavailable, etc.

However, what is unmistakably clear is that in the absence of any human

intervention population levels of BSLB over the past decade have fallen

substantially, perhaps even dramatically. Faced with such evidence of a

decline, and the great abundance of predators present, scientifically-minded

ecologists would hypothesize that it is a reasonable possibility that

predation, competition, and environmental factors are leading to a natural

decline in BSLB.

FPPP pointed to this preliminary data and the prima facie conclusions that

could be drawn from them and suggested that a reasonable course of action

might be to further investigate this possibility before concluding that

there was any necessity for human intervention.

N.B. An instructive point: in missed opportunities: Ricciardi correctly

takes me to task for not supplying sufficient data in a press release [17] pertaining to predators of BSLB in PPP :

"They did not say whether these groups contain the same species that

evolved behaviors and mechanisms to attack T. fuscum in Europe, yet their

press release falsely suggests that the park is replete with the beetle's

co-evolved enemies ..."

The fact of the matter is that science does not happen overnight whereas

preparations for the cutting of trees were proceeding at a feverish pace.

It takes some considerable time, for instance, to determine species of

insects to answer such questions.

What then does a responsible ecologist do? Proceed with all of the

requisite research and publish the data some years after the fact, or

bring forth preliminary indications, which can make at least a provisional

case for further research, perhaps forestalling unnecessary destructive

and irreversible actions? How does science with its time-consuming demands

of research, peer-review, and publication have even a hope of making a

contribution to a public-policy debate of this kind when a scant matter of

weeks after the "discovery" of this species in the Park, plans were

already underway to cut 10,000 trees. This salient issue of the

intersection of science, public policy, and environmental concerns, worthy

of considerable discussion in this context, is entirely missed by

Ricciardi.

The position of FPPP has been that there was no need to panic. By doing

even a little of the requisite research that might bear on the issues

involved, it would be possible to develop a better informed course of

action more likely to succeed, rather than cutting first and asking

questions later.

So-called Fallacy #2: The BSLB has been here for years without causing

problems, so there's no need to be concerned about the future.

A second straw man. Friends of Point Pleasant Park have never argued this.

Mr. Ricciardi mentions "lag period of logistic growth" implying my

supposed "ignorance" of this concept in:

"This species, moreover, has certainly been found in the park since 1990,

quite possibly since 1984; and indeed possibly even earlier than this. No

cataclysm has ensued."

|

The Brown Spruce Longhorn

Beetle, Tetropium fuscum.

|

In fact, as an ecologist I am not ignorant of the concept, however, what

this 'fallacy' shows is ignorance of the data, which indicate quite the

opposite conclusion; namely that populations of BSLB in PPP are in

significant decline. Neither I nor FPPP argue the syllogism that the

presence of BSLB in PPP - for however long or short a period of time - is

any necessary indicator that there should or should not be any concern

vis-a-vis the future. We argue instead that the ecology of the species

itself, the extensive research done to establish such, and its significant

natural decrease in the field here, all point in the opposite direction.

The shoe, rather is on the other foot. If one wants to claim that

cataclysm will or may ensue, one should be prepared to offer some very

compelling evidence. This evidence is conspicuously lacking.

So-called Fallacy #3: The BSLB had the opportunity to arrive in the 19th

century, so it must have been present since then.

Yet another straw man. While others may have made this baseless claim,

neither FPPP nor I have ever argued this, nor would we since it is

obviously false. As the previous quote of mine that Mr. Ricciardi cites

clearly indicates, there is only documented evidence of the presence of

BSLB since 1990, although the number of specimens taken then, and the

extant of their distribution, indicate that the beetles had clearly had

been here for several years previously. In the absence of evidence it is

impossible to draw further conclusions as to the duration of its presence

here.

Fallacy #4: The BSLB isn't a problem in Europe, so it won't be a problem here.

The only one of the points that Mr. Ricciardi's makes which actually has

some relation to anything that FPPP has argued, although not in the form

quoted by Ricciardi.

Ricciardi says that:

"These assertions are based on a fundamental lack of understanding of the

difference between native and exotic species-a difference appreciated by

most ecologists, but unfortunately not by the general public nor by some

environmental activists."

Ecologists do not make such extreme simplifications. Perhaps Mr. Ricciardi

is unaware that approximately 15% of the beetle fauna of Nova Scotia

consists of introduced species. How many of these species are "problems?"

100% of the earthworm fauna of Atlantic Canada consists of introduced

species. How many of these are "problems?" The "problematic" Spruce

Budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) is a native species. Such examples are

legion.

Although there are clearly exotic species which have become problematic in

various contexts (Dutch Elm Disease (Ceratocystis ulmi), Zebra Mussels

(Dreissena polymorpha), Norway Rats (Rattus norvegicus), etc.) changes to

the environment can provoke the same effect in native species (for example

in Canada consider the Spruce Budworm, the Hemlock Looper (Lambdina

fiscellaria), Herring Gulls (Larus argentatus), Canada Geese (Branta

canadensis), etc.) In fact, what most ecologists appreciate is that there

exists no such simplistic one-to-one correlation between native = good;

exotic = bad. The vast majority of introduced species either quickly

disappear or, if established, blend quickly into the ecological

background.

Uncritical adherence to the "precautionary principle" would lead us to

raze our forests in a scorched-earth policy of ridding ourselves of

introduced organisms. There are, for instance, over 400 species of

introduced "exotic" plants in Nova Scotia [18]. To be sure, a few can be

considered as "pests" or "weeds" but the great preponderance are neither.

The UN codification of the Precautionary principle quoted by Ricciardi

states that:

"Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full

scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing

cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation. [19]"

However Mr. Ricciardi fails to understand that the first half of this

syllogism has not been shown. There continues to be a lack of evidence of

"serious or irreversible damage" And while, as Mr. Ricciardi points out,

"full scientific certainty" is too strong a conditional in deciding

whether to take remedial action, this has never been the position of FPPP.

In the context under discussion the balance has, rather, tipped far the

other way. That is to say that there is virtually no scientific evidence

that indicates that "serious or irreversible damage" will ensue and the

limited data on the ground here in Nova Scotia, the extensive European

studies, and the general biology of the species, all indicate the opposite

conclusions. To invoke the second half of the precautionary principle one

needs to establish the first. To do otherwise is to commit a fundamental

error of logic.

What FPPP has argued in relation to the European studies, in conformity

with the principles of good science, is that one doesn't reject or ignore

well-conducted scientific studies simply because they do not conveniently

fit with predetermined conclusions. The proponents of the

"cut-first-ask-questions-later" school of forest management have often

discounted, out of hand, all previous scientific evidence with respect to

the BSLB arguing the specifics of the situation here render all previous

research worthless. For instance:

"A British expert on the beetle claims it is unlikely to become a serious

threat. Does this person have any experience with red spruce, a species

not native to Europe? Can he tell us how the beetle behaved in relation to

red spruce introduced there? If not his opinion is not very valuable at

this stage. [20]"

This may be fine rhetoric but science it is not. This is in response to Dr

Hugh Evans Principal Entomologist in Forest Research in England who wrote :

"It sounds as if further survey work and assessment of the biology of T.

fuscum is needed, but I suspect it will not prove to be a major problem

and will join the existing T. cinnamopterum as part of the beetle

diversity in spruce forests. [21]"

|

The Eastern Larch Borer,

Tetropium cinnamopterum.

|

Ricciardi also states (without citing any evidence to back this claim):

"In Point Pleasant Park, the BSLB attacks not only Norway spruce (its

principal natural host in Europe), but also apparently-healthy native red

spruce, white spruce, and black spruce."

On what evidence does he base this claim? FPPP has always maintained that

in the absence of good evidence, it is far more plausible (given the

unanimous results of European research) to posit that the reverse is true.

BSLB and a whole host of native insects are feeding on severely stressed

and dying trees. To claim the contrary would require strong supporting

evidence. Where is it?

Despite claims, offered without supporting data that BSLB are attacking

white spruce, and black spruce in PPP, where is the evidence? In my not

inconsiderable time examining trees in PPP during the summer of 2000, I

never so much as saw a single black or white spruce (few of them that

there are) which exhibited the resinosis or exit boreholes much in

evidence on affected red or Norway spruce. If Ricciardi excoriates

"environmental activists" for making claims without sufficient evidence,

should he not hold the feet of the Canadian Forestry Service (CFS) and

CFIA to the same fire?

Casualties in Ricciardi's Analysis

If left unchallenged Ricciardi's fallacious "fallacies" might enshrine

this issue in altogether too simplistic terms. Ricciardi's simplifications

reduce:

- a complex discussion of the balance of sufficient scientific knowledge

versus prudent action;

- balancing the rights of many stakeholders (recreational groups,

naturalists, environmentalists, tourism interests, forestry concerns,

regulatory agencies, etc.) when it comes to the disposition of public

lands such as municipal parks;

- the need for transparency, clarity in the conduct of public agencies;

- the adequacy of currently existing legislation to address such

situations;

- the interpretations and implementations of the precautionary

principle;

- the role of science in a context where events outstrip its ability to

adhere to its conventional protocols; etc.

to the most simplistic and least informative common denominators. By

setting up such obvious straw-men for his own demolition, he sheds little

light on a complex and fascinating issue.

Were I so-inclined I, too, could construct straw men to demolish at

leisure. For instance:

"Its not overstating things to say the real environmentalists are the

civil servants struggling to save Canada's forests from the destructive

potential of this foreign invader, while the obstructionists who are

trying to ensure the beetle's spread throughout the continent are deaf

dumb and blind to all reason. Their emotional, irrational, nonsensical

take on this issue gives environmentalists a bad name. [21]"

Pleasant as that might be as a diversion, such indulgences are beside the

point. There are substantive issues here and a diversity of legitimately

held values and beliefs. It has been the case that pro-cutting pundits

have misconstrued the position of environmental groups like FPPP. FPPP is

concerned with the environmental health of PPP and of forests in general.

What FPPP is against is not the cutting of trees, but the notion of acting

before one knows what one is doing. FPPP does not call for the impossible

yardstick of scientific certainty, but for some degree of scientific

probability.

In the face of many studies that indicate this beetle is no danger to

healthy trees; of preliminary indications that the beetles are in natural

decline; with many predators and parasites conspicuously present on

affected trees; with a plethora of potential factors that can severely

stress trees in PPP (drought, salting of park trails, removal of

underbrush and consequent nutrient depletion of the soil, soil compaction,

etc.); with the legitimate concerns of many affected stakeholders in the

Park, FPPP posits the question: "Why panic?" There is not the slightest

evidence an incipient "population eruption" endlessly trumpeted by the

pundits of cutting as justifying immediate and precipitous action. FPPP

argued, and continues to argue, that working from a base of knowledge is a

far preferable position.

A second casualty is a balanced discussion of contending viewpoints. If

one takes Ricciardi's concern that, "resulting cacophony of conflicting

'expert' opinions confuses and frustrates the public," at face value, then

one wonders why he devotes no attention to the inaccurate, hyperbolic, and

panic-inducing statements made by some of the pro-cutting fraternity?

Statements not based on any scientific evidence. Ought one not to

challenge unsubstantiated claims made by both sides of a debate, for

surely what is good for the goose is equally good for the gander?

[A Scientific Sidebar]

What about the repeated claims that the Park was "infested" with BSLB and

then the consequent inability to find these infesting hordes? What of the

repeated failure of the CFS and CFIA to acknowledge that many other

insects could be responsible for the symptoms observed in Park Trees? What

of the inability to ascribe with any certainty the two symptoms (resinosis

and exit bore-holes) to any particular species of insect? What of the

plans of the CFIA to cut in mid-summer when all European researchers

recommend cutting at the end of winter or in very early spring? What of

the failure of the CFIA to establish if healthy trees were being attacked

by BSLB or if these were already profoundly unhealthy trees? What is cause

and what effect are surely at the heart of this debate and the CFIA has

failed to produce evidence to substantiate its position.

Public confusion can also be abetted by scientists who baldly assert,

"Trust me. I'm an expert. I don't need to produce evidence which the

general public wouldn't understand. You can take my word for it." This

debate has too often seen such posturing. Why, then, is any critique of

these missing from Mr. Ricciardi's article given its stated aims? Thus,

this one-sided treatment of the issue in Ricciardi's article does nothing

to dispel purported public confusion. Consequently Ricciardi fails in his

stated objective of, "promoting scientific literacy among our fellow

citizens."

Christopher Majka studied biology at Mt. Allison and Dalhousie

Universities and has worked as an ecologist on projects around the world

with Parks Canada, the Canadian Wildlife Service, CIDA, Polish Academy of

Sciences, International Biological Program, Operation Baltic,

International Crane Foundation, Persian Dept. of Environmental

Conservation, Edward Gray Institute, Instituto National Pesquesas de

Amazonas, Program of Integrated Research on Pelagics, Ocean Search, NB

Dept of Natural Resources, etc. He has worked as an entomologist both for

the New Brunswick Museum and Mt. Allison University; has been doing

research on lepidoptera in New Brunswick for over 30 years, and has

founded several prominent Internet entomology resources including the

Usenet groups sci.bioentomology.lepidoptera and sci.bio.entomology.misc

and Electronic Resources on Lepidoptera [23].

[1] http://biotype.biology.dal.ca/biotype/2001/feb01/tr.bslb.html

[2] Plant Protection Act. Section 3.

[3] Specimens deposited or being deposited with the Nova Scotia Museum. Publications in progress.

[4] Wojciech Zabecki, personnel communication, July 12, 2000.

[5] http://niskwww.nlh.no/entomolo/barkved/trebukk.htm

[6] Dobesberger, Erhard John. May, 2000. Plant Health Risk Assesment: Brown Spruce Longhorn Beetle Tetropium fuscum (Fabr.). Plant Health Risk Assesment Unit, Ottawa, Ont. 35 pp.

[7] Berryman, Alan A. (1972) Resistance of Conifers to Invasion by Bark Beetle-Fungus Associations. Bioscience 22(10):598-602.

[8] E. Gorton Linnsley (1961). The Cerambycidae of North America. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. pp. 24.

[9] Specimens deposited or being deposited with the Nova Scotia Museum. Publications in progress.

[10] For instance the genera Thanasimius, Enoclerus, and Phlogosternus are all specifically indicated in Linsley (1961) as "North American Cleridae Predaceous Upon Cerambycidae" and Thanasimus is specifically noted as a predator of Tetropium.

[11] Linsley (1961) specifically highlights six species of Atanycolus as known parasites of cerambycids. Zenon Capecki (1979) Occurrence of Tetropium and their parasites in Poland. Sylwan 12: 47-58; found Atanycolus as a parasite of both Tetropium fuscum and T. castaneum.

[12] Arnett, Ross H. & Michael C. Thomas (2001) American Beetle (Volume 1). CRC Press, Boca Raton. 443 pp.

[13] Nova Scotia Dept. of Natural Resources. Tetropium fuscum Trapping Survey Results 2000.

[14] NS Department of Natural Resources data. Manuscript entitled "Trapping Survey"; 44 pages & Nova Scotia Dept. of Natural Resources. Tetropium fuscum Trapping Survey Results 2000.

[15] Stephanie Robertson (1990) Point Pleasant Park, Halifax, Nova Scotia Bark Beetle Survey. Halifax Field Naturalists. 39 pp.

[16] Deposited with the Nova Scotia Museum.

[17] Christopher Majka. Cutting Program Threatens Predators and Parasites of Brown Spruce Longhorn Beetles. FPPP press release, July 31, 2000.

[18]Roland,A. E. & E.C. Smith (1969) The Flora of Nova Scotia. N.S. Museum, Halifax, N.S. 746 pp.

[19] Principle 15 from the United Nations Conference on Environment & Development (Rio Declaration), http://www.igc.org/habitat/agenda21/rio-dec.html

[20]Parker Barass Donham. Daily News. June 21(?), 2000.

[21] Hugh Evans. Help the trees more info. Email of June 12, 2000 (widely circulated)

[21]Parker Barass Donham. Judge out on a limb with halt order. Daily News, August 20, 2000.

[21] http://www.chebucto.ns.ca/Environment/NHR/lepidoptera.html